|

|

||||

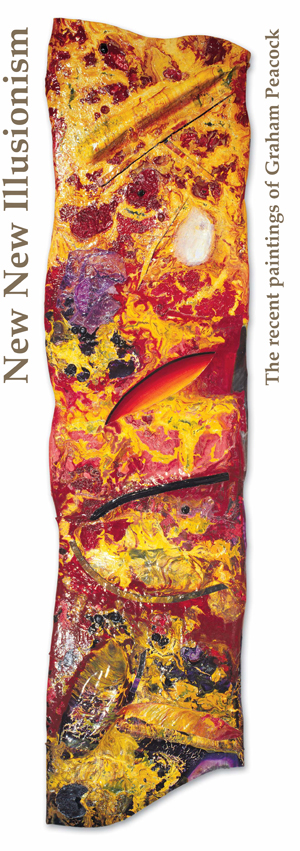

Goodness Garishby Leide Muehlenbachs Eminem (and Adrian Brody at the 2002 Oscar’s) says you get one shot. Maybe, maybe not or perhaps you get one life with a lot of scatter shot. Whether cannonball or scatter, Peacock’s one shot could be summed up as a go-for-broke attitude whenever he crosses the threshold of his studio, an awareness that creation, artistic or other, from conception to birth demands perfect aim. This attitude works for him, by now, subconsciously and is embedded in the labyrinthine, no holds barred technical processes he has nurtured over many years. The one thing Peacock is not is uptight and it might help him glimpse the future, its possibilities at least. Artists, especially abstract painters, practice and practice so they can open the doors to unfettered expression and continually surprise themselves. Most don’t. Although Peacock works in Edmonton, Alberta where abstract painters and sculptors are plentiful and whose reputations en masse have been both mocked and praised, at times to laughable exaggeration, it remains, with exceptions, artistically conservative. As a painter, Peacock, above all, is the odd man out which has fortunately strengthened his resolve and made him see --and exhibit successfully--beyond the Prairie horizon. The culprit responsible for tame painting could very well be landscape itself . From the Group of Seven to the continued, commercial success of landscape painters from sea to sea, who can blame the artists? The country with a maple leaf on its flag is synonymous with landscape, awesome, harsh, lyrical, above all invigorating and one with its history. Many Canadians have a personal relationship with the earth and the sky. This, can, however, become an excuse for mediocre painting whether representational or abstract.. Being right like nature here becomes a meaningless platitude. Many painters remain at the mercy of landscape, whereas it has motivated Peacock to be merciless with his materials. When an eminent N.Y. critic lamented some years back, ‘”Those poor artists in Edmonton still think gel is the answer,”’ Peacock wasn’t at issue. Sure there is gel in his paintings, but there is also enough interesting stuff to fill several Saks Fifth Avenue’s. He has a primitive need to go way beyond the few swishes of thickened pigment, the few scoops of ground-up rock filler or arthritic finger painting so often seen in Edmonton. He is like a hunter-gatherer when it comes to his material sources. Of course, his work has been criticized as garish and it’s often a garish rev-up for him, too. Garishness, gorgeous garishness, becomes a fortuitous stepping stone, a way to arrive at a unique harmony in the work, basically an intentional exercise in personal taste. However complex Peacock’s paintings have been, they have also been marked by colour that is bright and clear and unabashed as if lit by some Fauve strobe light. Not just great colour but colour that is great. And colour that has evolved by way of the countless hard-won battles that haunted Post-impressionism and all it’s peripatetic off-shoots. Colour perceived by some (even today?) as a scare tactic. Pollock’s favorite T-shirt might have read I am nature. Peacock’s could read I am earth. An intensely exploratory approach to all available materials has resulted in work that replicates universal physical properties, especially those of land forms. How can what is magical in nature become threatening for some in a Peacock painting? He is the master dryer of paint with more cycle options than a Maytag. But just imagine what various cooling times, even of the same material, have produced on the earth. Diamonds, snowflakes, Devil’s post piles; a lava flow that is never uniform in consistency and dries into phenomenal configurations granted sonorous Hawaiian names. By unfair comparison, Peacock is a babe in the woods but the knowledge he has gleaned and is delighted to use evolves into pictorial delight. Clement Greenberg dubbed some of his paintings in process ponds but as they dry, transform and develop his signature crazing they look like evaporating mud puddles from which all the frogs have gone on to become princes. Harsh is the environment Peacock has had to work in and one wonders how often he can take having his work referred to not only as super-monster deluxe pizzas but regurgitated ones as well. Such is the level of artistic discussion that goes on behind the back of this intrepid artist. On the other hand, if Peacock sees a badly imitated Olitski (they reproduce like rabbits in Edmonton), he certainly knows it has nothing to do with the real Buddha. He is so impatient with status quo, I almost split a gut laughing at one exhibition, when he said a certain artist would be painting on the back of the canvas if that artist painted any flatter. In the art world, those who don’t dare to dare will be ignored. Envy is a supreme motivator, a changeling that can masquerade as criticism. Scorn directed at extreme physicality is nothing new, historically suffered most prominently by Auguste Rodin, whose own avoidance of flat, smooth surfaces speaks volumes here. Instead of carving and polishing, he pulled and squished and mangled his surfaces to a level of expressionism that horrified the critics but freed up another generation of sculptors. For Rodin, human essence was stuck hard on the inside and demanded much physical coaxing to reveal it convincingly in a static sculpture. Likewise, Peacock often speaks of extracting expression or painting from the inside out. Mean and nasty as everyone was to Rodin, he managed to believe in himself because An art that has life does not restore works of the past, it continues them. 1 And that´s Rodin, shooting straight from the beautifully gnarled hip. 1 Auguste Rodin, The Cathedrals of France. Beacon Hill Press, Boston, 1965, p.65. |

|||||

|

|||||