|

The Intermezzo Work of Graham Peacock

by Marcel Paquet

Graham Peacock’s work deploys its strange and intense beauty between the things that arise from nature and things that come from human culture, that is, the multitude of objects made by human hands. The former, Aristotle observed, carry their movements within themselves, while the latter derive their reality from actions that are outside of themselves. They do not exist in and of themselves, but rather arise from an outside power, located within the body of man. However, among the multiplicity of objects produced by human technique, there are those that are destined for no use, other than to surprise the eye, to hold it in suspense, to cause it to marvel. Do they stray from a well-organized cultural domain and its signs, codes and declarations to turn back towards nature? Do they come from nature and head towards culture, or do they stop halfway there, defiant and denying in advance everything that can be said about it?

Artworks fall into this undecidable difference and never abandon it; Graham Peacock entered this nature of art unhesitatingly and it is out of the question that he should leave it.

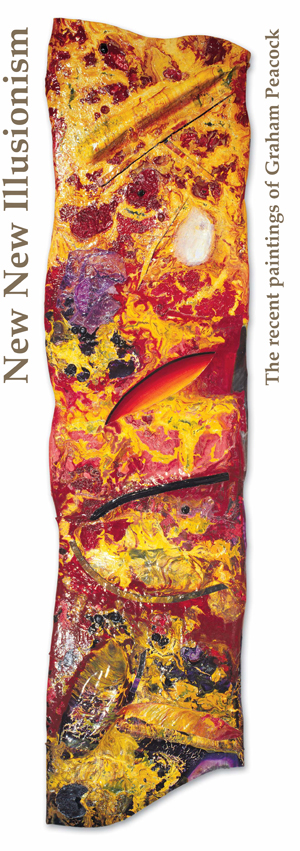

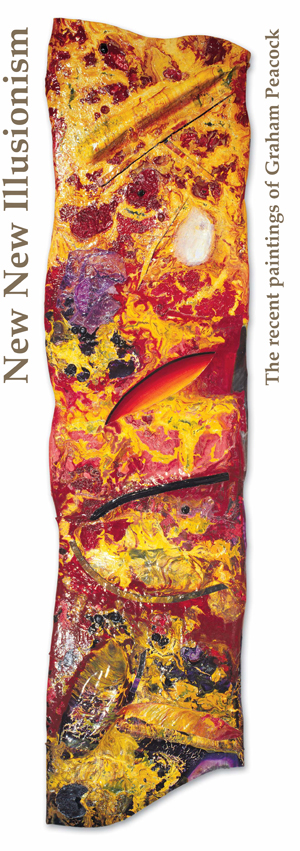

In all their aspects, Graham Peacock’s works seem to grow from the earth, resplendent like multicoloured lava, divine, mythical, sacred, arising from a world that existed before ours, which was already no longer chaos but was not yet that of our ordered, cultured, scientific, conscious, reasonable, human, annoying, posed, conventional, sad universe. Graham Peacock’s work stands out in refined culture like a beneficent lightning bolt that contradicts all the possible points of view. This artist does not try to imprison time in an eternal frame, but, like the New New Painters, an inspired and enthusiastic cohort stretching themselves into unexplored territory, consisting of the best and most adventurous of pictorial Europe and America after World War II, who discovered the novel potentialities of materialist and expressionist abstraction, one of the true bridges spanning the Atlantic, an obscure Euro-American rainbow fraternity, to-ing and fro-ing within itself, much better welded and much better situated than diplomatic agreements and muddles can ever be, but, like all the New New Painters, he does not copy or recopy anything, he allows informal powers to step into the light, he allows himself to be filled by forces that become works without having to trap himself in a Euclidean box, without having to end up or to die inside a frame. In looking at Graham Peacock’s works, the use of this ancient form inherited from the Renaissance seems to be a sign of artistic backwardness, as a superannuated vestige arising from a geometric order that no one trusts anymore. Except perhaps to reassure themselves, when worry overcomes thought and we suddenly start to speak and see like everyone else, like whistling a tune when the night we are walking through is too dark. Like the magnificent tribe of the New New Painters, Graham Peacock is from the point of view that, like the very cosmic William Gruters and the free, free Irene Neal, goes the furthest, serenely, the furthest outside this cutting constraint, like a previous style of art to which he never belonged. This is the art, which for reasons unknown to all, submitted itself to Plato’s idea of art. Whatever this problem may be, Graham Peacock’s work has never allowed itself to be trapped by a cultural vision of art: Free, he lets the freedom of art go as far as possible. This may seem like insouciance, but this is not the case; this is a serious ethical responsibility, a responsibility without which, Robert Motherwell said so accurately, “the painter would be a mere decorator”.

Graham Peacock’s ethical aesthetic is to lead us back to contact with the elemental forces of nature, not to maintain the rupture between the Subject and the Object, the source of so much uneasiness. His painting does not give us a speculative image of our biases, but manifests all the aspects of life that not only resists them, but also affirms itself in complete independence. Gödel, Einstein and the quantum realities of infra-atomic physics have demonstrated there is no longer any single truth in mathematics or physics: should there be only be one uniform, universal method of painting? How foolish, how conservative are those hearts that are closed to the beautiful incandescences of Graham Peacock’s painting, to his luminescent energies that reveal to us how much the blackness of night is only a veil hiding an infinite richness of multicoloured treasures, brilliant, resolutely incalculable. The goal of this art is not in the beauty of its shapes but in the forces of life and in the sensitivity that gives it solidity: it engages thought on the path that ranges from “I think” to the “I feel” hidden within, wrapped around it; freed and unfolded for itself, this continuing feeling abandons any Me-Me to its poor, its empty, its cold and sinister abstraction. In this way, Graham Peacock cultivates an informal moving incoherence that leaves no vision and rest in the illusions of the moment. His work is one of inexhaustible and surprising richness; it fights nothing, it does not confront, it does not operate through frontal assaults and face-to-face combat: it slides right beside filters, walls and windows: it is painting of the great outside, of sensitive fullness discovered directly from the film of the visible.

Its films, its cracks, its colours, its flows confer an opulent and warm substance to that which maintains an invisible transparency to the knowledgeable and self-satisfied eye. Graham Peacock gives to the visible a full, sensitive and flexible cohesion; it is an art with a great gentleness, but also with an uncommon resistance. It is peaceful art, yet one that generates energy, an inducer of great transportations in the viewers’ spirits. It is as if they go unmistakably from the status of voyeurs to that of seers!

Graham Peacock’s work moves one without taking any detours, without embellishments; it affects without being sentimental or using seductive ruses. It goes straight to the point, “zur Sache selbst”, as Husserl said of the phenomenological approach, well, that is how Graham Peacock paints. With no regard for socially obligatory themes, he works with an honest ease, one that is not exempt from hard work and procedures that were patiently developed, notwithstanding their irretrievable singularities for insensitive intellects.

With Peacock, the gaze is obviously never enslaved to a geometric vanishing point that functions as a stop sign. On the contrary, he practices a form of painting that gathers infinity within itself rather than protecting itself from it. It is an art that extends itself, with a multidimensional expansion; it is not an art of limits. To have an overall perception of it is impossible and that is why it invites us to a marvellous conversion of the gaze, to an infinitely liberated approach to reality itself. There is nothing inert in this work. It advances and builds itself without structuring itself as something to which life would come to add itself to like a additional touch or as though by accident; it is completely about life, completely an energetic and genetic process within which the end has no end and mobility is an organizing principle of randomness. It would, in fact, be incorrect and unfair to see only an irrational and irregular casualness in this work. Certainly, it has an element of pure research within itself but there is also a will to change our perceptions, to diffuse them in order to broaden them, to make them less static, less sure of themselves, less frozen, less immoral.

Our world is stripped of stable spatial coordinates. Also, our perceptions must defy the factual rigidities that give the impression of knowing everything about everything. Graham Peacock’s work leads our perceptions towards a greater humility, to more humanity; it reminds us of the degree to which the visibility of the world is greater than the views we have of it, the degree in which the world is intensely mysterious beyond the reaches of our limited knowledge. It shines outside of us, a mystery that is also within us and, in my opinion, it is this sundered unity that Peacock’s painting is endeavouring to restore, to restart, always in the same way and always differently. As though the unitary linkage never really held and had to be remade indefinitely, to be redone, which might be interpreted as a failure or a loss that this painting also transports an element of humour, a wink, a lightness. Within this beautiful and powerful abstraction, is a mocking distance, like an indefinable smile which prevents one from being too serious or as if carried away by a wind that is too strong. In Peacock’s work, we find all the metamorphoses of metaphysical matter, but with a kind of elegant distance; a way to ensure that we do not transform tragedy into drama, a way of saying that it never quite works out, a way of saying as my daughter, Joanna, likes to say “It’s not that serious”.

|

|

|